Patents and Progress: What IP tells us about the future of synthetic biology

When people talk about the future of synthetic biology, the conversation often turns to lab breakthroughs, new venture funding, or emerging start-ups. Yet there is another lens that offers perhaps the clearest view of how science is translating into business: patents. They are more than pieces of legal paperwork. They are signals of intent, markers that an idea is moving from the research bench toward the marketplace.

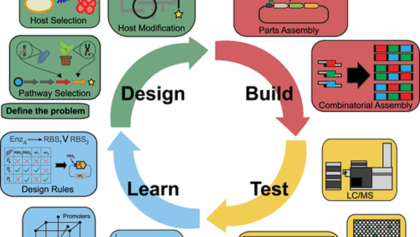

Potter Clarkson, a Gold Sponsor of SynbiTECH 2025, has recently released one of the most comprehensive analyses of synthetic biology patents to date. Analysing two decades of European Patent Office filings across 40 technical categories, it reveals where momentum is building and where future investment, regulation and collaboration may be most needed. Some of the strongest growth is visible in areas tied to sustainability.

Synthetic Biology Patent Landscape Report

Patent activity around engineered microbes for industrial enzymes, alternative proteins, packaging materials and textiles is climbing, reflecting the urgent push for low-carbon solutions. Therapeutics remain another powerhouse of innovation, spanning engineered bacteria for cancer treatment to novel antibody and drug delivery systems. Taken together, these filings show that synthetic biology is not only expanding in scale but also diversifying in application.

The geography of patents also tells an important story. Europe and the UK continue to carve out advantages in their ability to protect certain naturally occurring organisms, an option not available in the United States, where laws restrict the patenting of natural entities. This divergence shapes how companies approach global strategies, with Europe offering unique opportunities in areas such as microbial discovery.

- Sustained growth in filings: Synthetic biology patents at the European Patent Office have increased at a compound annual growth rate of 8.7% over the past decade, significantly faster than the wider biotechnology sector.

- Therapeutics powering ahead: Therapeutic applications dominate patent activity, with antibodies, antimicrobial peptides and drug delivery systems all featuring in the top ten categories. Yet non-therapeutic areas are also highly active, with genetically modified microorganisms ranking fourth overall, biofuels seventeenth, and transgenic plants twentieth.

- Genome editing’s rapid ascent: Patent filings related to genome editing, particularly CRISPR, have surged with a 68.3% compound annual growth rate, marking it one of the most dynamic areas of innovation.

- Innovation beyond healthcare: While established fields like biofuels are levelling out, new momentum is visible in waste-to-bioplastics, hydrogen generation from non-carbon sources, and alternative proteins reflecting the diversification of SynBio applications.

- The UK’s Competitive Edge: The UK holds the fifth position globally for specialisation in synthetic biology patents, ahead of Germany and France. Growth rates in both biotechnology and intellectual property activity are outpacing broader national averages, underlining its strategic role in the sector.

For full insights check out the Synbio Patent Landscape Report 2025.

An Industry Perspective

For Sara Holland, a patent attorney who has spent the past twelve years working with founders, spin-outs and research teams, these findings resonate with her day-to-day experience. Speaking from the perspective of someone who advises companies at the very start of their journeys, she sees intellectual property not as a secondary issue but as the foundation upon which everything else rests. “You can have a brilliant idea,” she explains, “but if you haven’t protected it, there’s nothing of real value to build a business around.”

That reality often collides with the habits of academic life. Publishing too early can extinguish the possibility of patent protection, yet many researchers are under pressure to share results before considering commercial implications. Holland describes the light-bulb moment when founders realise that publishing without patenting can close the door on turning discoveries into viable products. The same risk applies in the commercial world. She recalls a recent case where a promising product had already been launched on the market before protection was sought. By then, only the manufacturing process could be protected, not the product itself.

Funding only adds to the complexity. Most early-stage companies face what Holland calls a catch-22. Investors often want to see patent protection before committing capital, yet filing robust patents usually requires data that start-ups cannot generate without funding. Spin-outs from university labs may have a head start with existing data, but independent founders frequently face the costly challenge of proving proof of concept before they can secure protection.

Despite these hurdles, the trajectory of the sector is unmistakably upward. Compared to a decade ago, there is a far richer ecosystem of accelerators, networks and peer support. Founders are leaving academia earlier, driven by a desire to see their research make a real-world impact rather than sit in a journal. The sheer number of start-ups has grown dramatically, and with it the collective experience of navigating scale-up, regulation and intellectual property.

Patents, in this context, are more than defensive tools. They act as indicators of where commercial potential lies, pointing investors toward growth areas and signalling to policymakers where regulatory frameworks may need to evolve. While academic publications remain essential for advancing science, it is the patent filings that reveal which innovations are moving toward products, partnerships and market entry.

The lesson is clear. For founders, protecting intellectual property is not an afterthought but a vital first step in commercialisation. For investors and policymakers, patent data offers a roadmap of where innovation is clustering and where support structures are most needed. And for the wider synthetic biology community, the combination of robust analytics and practitioner insights shows that the field is entering a new phase, one defined by commercial seriousness as much as by scientific creativity.

As Holland puts it, “All you’ve got of actual value at the start is your IP. You need to look after it from day one.”

For anyone seeking to understand where synthetic biology is heading, the patent landscape provides a powerful guide. And with sustainability, therapeutics and advanced materials all showing rapid growth, it is clear that the sector is no longer a niche of research interest but a commercial force shaping the industries of the future.

Later this year, Sara Holland will present an 18-month update to the report at SynbiTECH2025, offering fresh data and analysis on how these trends are evolving. Her talk, delivered on behalf of Potter Clarkson as a Gold Sponsor of the conference, will provide an inside look at which areas are accelerating, which are consolidating, and where new opportunities may be emerging. For anyone interested in the commercial future of synthetic biology, it promises to be an essential session.